Event

This paper examines filmic representations of trains in the PRC from 1949 to 1976, as a figure for modernization and the formation of a national body. Within these narratives, I examine how PRC cultural production focused on “citizen science,” how the train was used as a metaphor for the formation of a national body, and how these works depicted the formation of a national body as a form of bodily discipline.

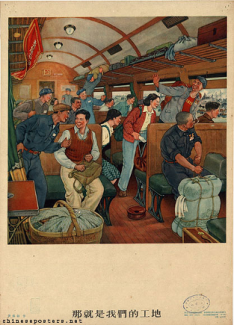

During the 1960s in the PRC, “science” shifted from a rationalized, bureaucratic endeavor focused on understanding natural phenomena through experimental models to a grassroots endeavor aimed at the resolution of pragmatic issues. Midcentury Chinese depictions of science valorized amateur production and dissemination of scientific knowledge, and depictions of trains, railroads and the lives of their passengers were no exception. These narratives also focus on the construction of what I term “quotidian utopias” – utopian spaces carved out in the contemporary moment through a communal investment in mutual sacrifice. This space becomes a metaphor for industrial and social progress, represented by the broad swaths of working class proletarian passengers. Key among the laboring masses aboard the train are the train conductors, attendants, and rail workers. These workers are often depicted as learning new, Maussian “techniques of the body” in service of their duties maintaining the trains and the social welfare of the passengers. Often, contributing to the health of the train as nation is figured as necessitating the sacrifice of the individual – through losing sleep, or worse.

In closing, the paper argues that contemporary sf author Han Song’s novella, “My Country Does Not Dream,” can be read both as a metaphor for the breakneck pace of work in the contemporary market economy, and for the valorization of sacrificing the body to the machine during the Mao era.